Let’s use AI for good instead of evil.

(nb this is my first draft. When you encounter things that need more explaining, please use the Hypothesis annotation bar at right, while being logged into our HIST3812 reading group, to indicate where things are unclear for you or require deeper discussion).

Some of you might want to explore the power of what popularly is called ‘AI’, but specifically, is a large-language model called GPT3. You may have come across this by reading sensationalist articles like ‘This article was written by an AI!’ or, ‘Students Are Writing Essays Using AI!’

In truth, yes, we could get GPT3 to write an essay. But it would be the most boring thing to do. In this tutorial, we’ll generate a comic strip or a graphic novel. But that’s the easy part. The hard part will be to guide the AI to building something meaningful. And for that, we’ll adapt/adop Jeremiah McCall’s ‘Historical Problem Space Framework.’

A quick word on how GPT 3 works.

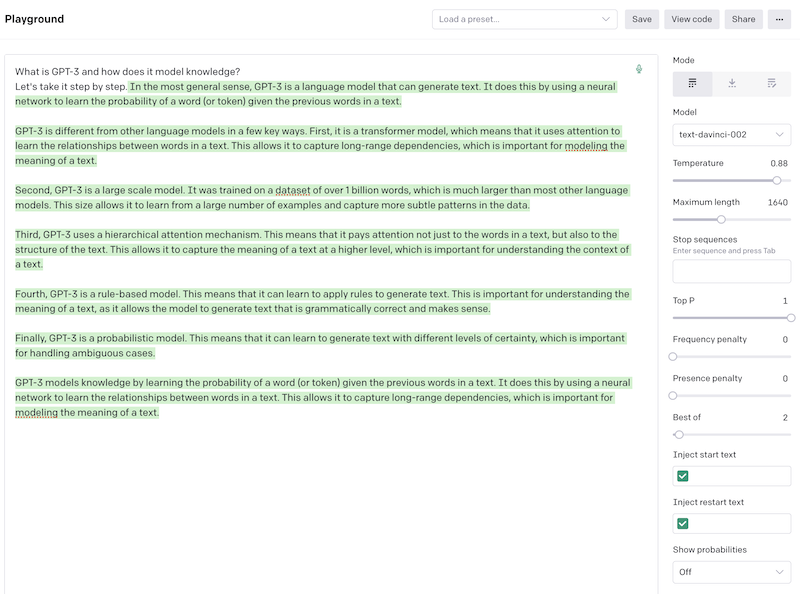

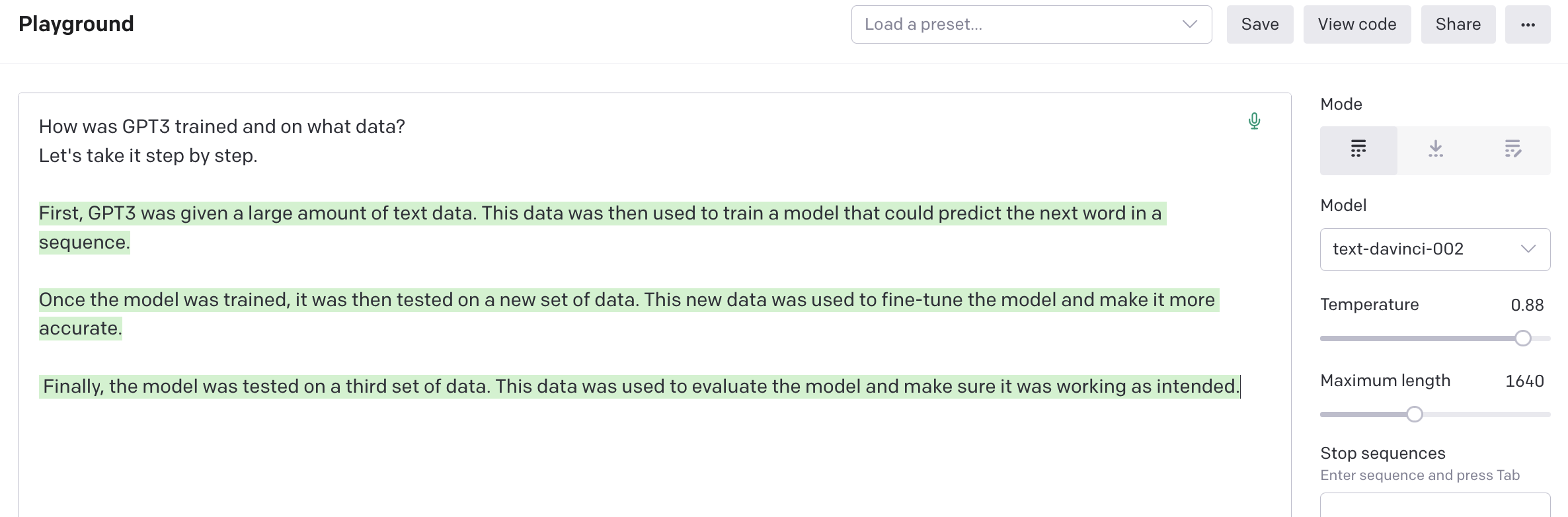

I figured the best way to explain this to you would be to let the AI do it itself. Below is a screenshot from the GPT3 playground from OpenAI.com. The clear text is what I wrote; the text highlighted in green is what the AI responded with:

What GPT3 neglects to tell us are the sources of the data. Apparently, it was on millions of websites, the most recent of which were published (put online) in 2021. Wikipedia is in there. Reddit is in there. Personal blogs, academic papers, government websites, newspapers, 4chan… well, hopefully not 4chan. But it’s a lot. Then:

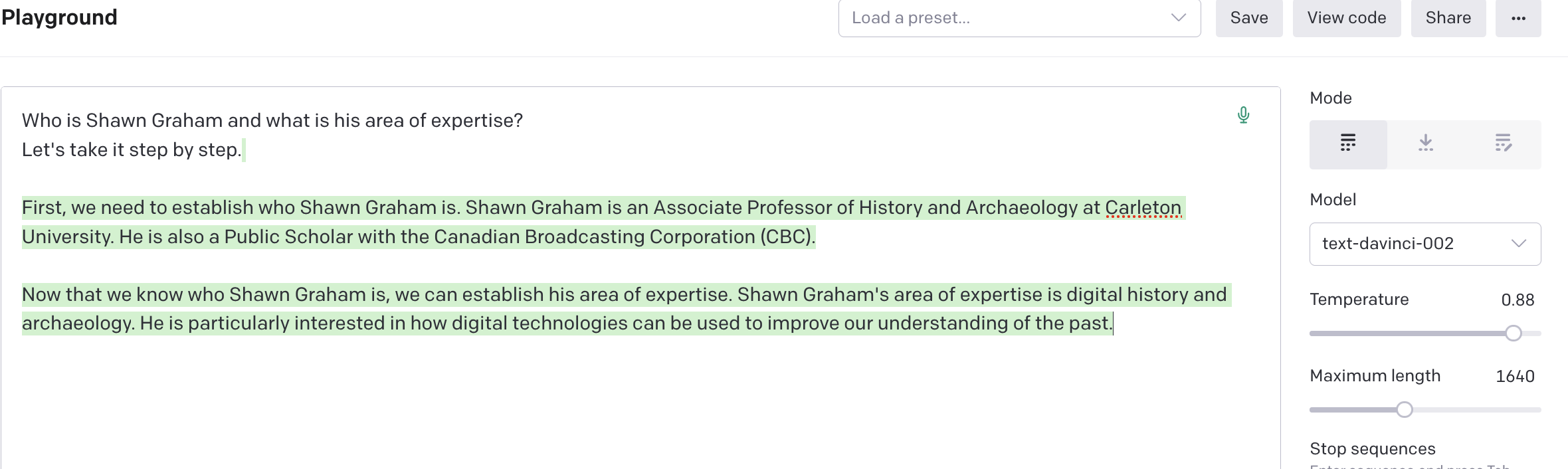

There’s an awful lot that GPT-3 knows. But sometimes, it gets… creative:

I was an Associate Professor, up until July of 2020 when I was promoted to Full. And yes, I do do digital history and archaeology, and yep, I am particularly interested in expanding how we understand the past. But I’ve never worked at the CBC (although CBC, if you’re reading this, maybe I could host a show…?). Do you see that ‘Temperature’ slider, way at the right hand side of the ‘playground’ interface? The closer that gets to 1, the more creative GPT-3 gets in its attempts to answer the question. If I dial that down to 0 (ie, just tell me what you know GPT-3, don’t get cute), it responds: Shawn Graham is an Associate Professor of Digital Humanities at Carleton University. His area of expertise is digital history and culture, with a focus on public history and the use of social media and new media technologies in historical research and public engagement.. I google that phrase, just to make sure that GPT-3 isn’t plagiarizing anyone (more on that in a moment) and see that the description appears to be GPT-3’s own writing and yes… it know who I am.

This is both creepy and cool. I can ask it about Louis Riel (just swapping out my name for his) and it answers: Louis Riel was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a leader of the Métis people of the Canadian prairies. He is a controversial figure in Canadian history, and his expertise was in politics and government.

What Can We Do With This?

Asking what we can do is not the same as asking what we should do.

GPT-3 has been used to power chatbots, develop Q&A systems, write code, design websites (you can give it an example of html and then ask it to write the markup to achieve particular effects)… you can find many examples with a trivial amount of googling. I’ve already indicated though that I find ‘essay writing’ the least interesting feature that GPT-3 can do because this is a class about playful engagement. Wouldn’t it be interesting to fine-tune GPT-3 on the diary of William Lyon MacKenzie King and then ask him questions about his life? I mean, he was into seances and believed spirits could speak with the living (if you check the schedule, we’ll look at how to do this with a smaller version of the same kind of AI, GPT-2, via this notebook by Max Woolf; the advantage of using GPT-2 is that since the model is smaller and older, it doesn’t cost us anything to use; more on price in a moment).

That raises an obvious ethical question: what if the model says something that MacKenzie King would never have said? Or even worse, considering King’s antisemitism, something he did say/think or plausibly could’ve said?

That’s why it’s not enough to just make something with GPT-3 and similar models. There are huge issues to think through.

Think through what you do in terms of HPS

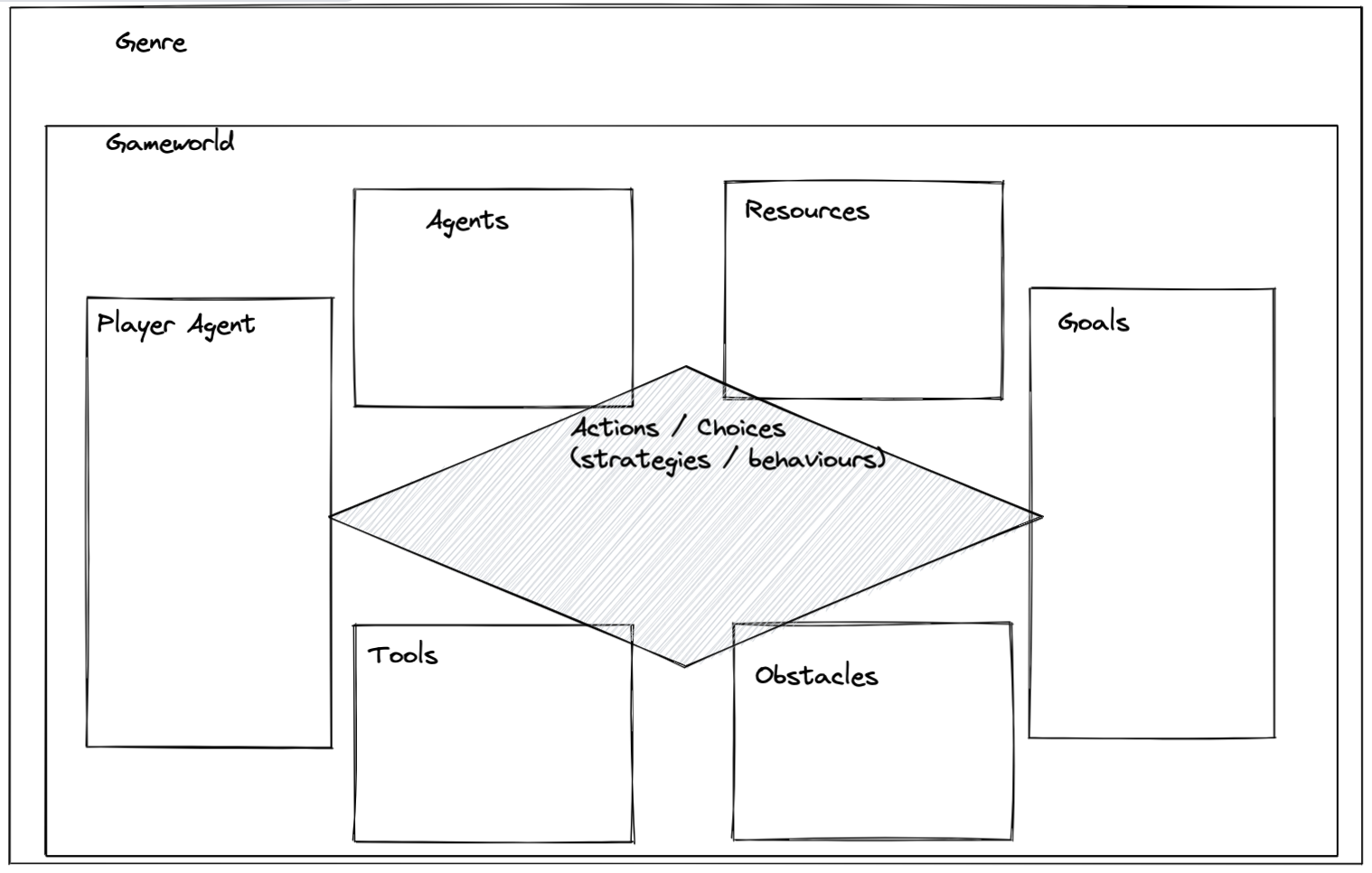

McCall’s HPS framework gives us a model for mapping out the elements of an interactive experience (which in this case also includes training and fine-tuning data) to see what kinds of historical experiences are possible. If you haven’t read this, this, and this yet, now’s the time to stop and read them.

Go ahead, I’ll wait.

McCall draws attention to the way ‘genre’ conventions in games curtail the kinds of ideas that can be realized in games; games are mathematical systems of interlocking parts, so once we start narrowing down those parts they can only mesh in particular ways. Jayanth’s piece suggests that the material conditions of game design also play a role in what kinds of experiences can be imagined, reflected, and realized in games. What’s the analogous situation here? For our present purposes, games and large language models are both representations of the/a world. And if we are fine-tuning on the work of someone like King, the material conditions of his life and world are going to turn up: we have to think hard about the intersection of King’s antisemitism with the ways antisemitism emerges in our own day and age (in the training set, in the ways the model might draw connections). A modified ‘historical problem space framework’ can help us map these out.

Take some time now to think through the various layers of interesecting systems and information (data) at play, and begin sketching out a modified version of the HPS framework.

‘Genre’ perhaps equals the kind of experience you want the AI to generate. What are the conventions?

‘Gameworld’ perhaps equals the way a person might encounter the experience. Did you generate text for a visual essay? Did you embed your experience as an app? Is it powering descriptions for images?

‘Actions/choices/strategies/behaviours’ perhaps still obtains: what can the person who encounters this experience do? Similarly, what are the ‘goals’ that one might have, if they encounter eg a chat bot: is it to stump the chat bot? Is the chat bot meant to cause the person to reflect on their own encounter with the past? (For this latter, see the work of Rousseau et al 2019.)

For ‘player agent’ perhaps we should think about who the ‘ideal reader’ is of your experience, as in Jayanth’s terms… are you designing for a person much like yourself? What’s your position in the world? How does that affect how you imagine one might approach what you’re designing?

The other blocks that constrain a game-based experience might be usefully re-written depending on the conventions of whatever approach you are taking. The key thing, after mapping all of these out, is to ask yourself, how do these elements all combine to enable some ways of curating the past and not others? What choices have they forced me to make about what is important? Form shapes content, McCall tells us, and the HPS allows you to formalize your answer to this question: ‘how did [you] employ [your] skills and talents in the medium to communicate the past in a [playful] history?’

I’ll admit that I often do before I think or reflect on what I’ve done. With digital techs, it often takes a long period of farting around with things before you really get to grips on how things work. But once you start getting a sense of the possibilities, that’s when it’s time to start plotting out how it all works.

Fart Around and Maybe Find Out?

For the rest of this tutorial, I’ll gently adapt Robert Gonsalves' tutorial on how to make a comic strip with AI.

Now, you may have taken HIST2809: The Historian’s Craft. The craft of what we do in this case lies in the construction of the ‘prompt’, sometimes called ‘prompt engineering’ (and note I can’t ask GPT-3 what ‘prompt engineering’ is because the term emerged after the creation of GPT-3 and the need to craft cunning prompts).

First thing’s first: Get an account with OpenAI. This will give you $18 worth of credits to play with. Everytime you create a generation, a microscopicly small amount of money pays for the computing time. (Speaking of computing time, the environmental impacts of training such models is huuuuuge which also prompts me to ask: should we even be doing this?).

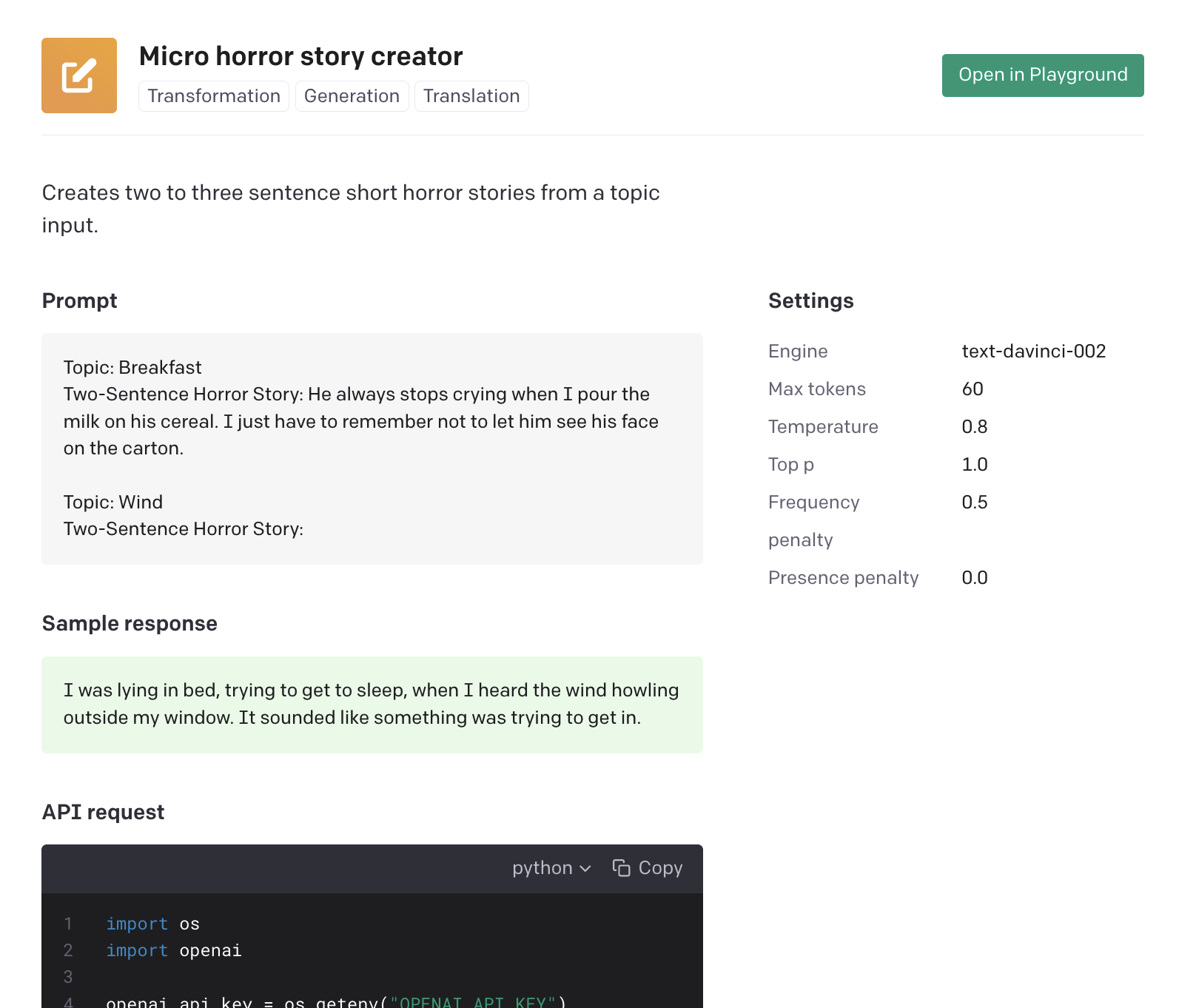

Then, you can examine the examples that OpenAI provides you. For instance, here’s the example for the two-line horror story generator:

The prompt tells GPT what topic we want a story on - breakfast - and it gives an example of what two line stories look like. Then, we continue to give the prompt what we actually want it to do - a story about wind. GPT reads all this and examines it billion-paramater space to find the probabilities of words that occur when this given pattern of words already exist. And then it completes the text…

So, let’s build a comic. Go to the playground, and in the text entry box, give it a prompt like this:

Create short wacky titles for a humorous comic strip about archaeology.

At the bottom of the playground box, you can hit the ‘submit’ button. At the right hand side, you can tweak the various elements. Give it a play! See what you come up with. You might have to re-run the generator several times to get what you want.

Now let’s generate some characters for this comic strip. Get rid of the previous prompt, and make a new prompt along these lines below; include the name you’ve chosen.

Create lead characters for a new comic strip about archaeologists called 'The Archaeologist's Handbook to Life'.

My attempts eventually created ‘Amy’ and ‘John’; it described Amy as a bit of a go-getter, and John as a bit of a goof-ball (…is GPT-3 pulling on popular conceptions of archaeology here? I had to regenerate several times to get rid of various Drs Jones who were into adventure…) . At first, it also included ‘Dr. ' as part of the name, but I found the subsequent results were quite stuffy (which says something about GPT-3’s training materials…). For the next prompt, we’re going to create a scene:

Create a scene with humorous dialog for a comic strip about archaeologists called 'The Archaeologist's Handbook to Life'.

Characters:

Amy: A highly respected archaeologist who is always looking for new and innovative ways to do her job. She's not afraid to speak her mind, and she's always looking for new challenges.

John: Amy's colleague and friend. He's a bit of a goofball, but he's always there to lend a helping hand.

Scene:

I added the ‘Scene:’ to remind GPT-3 not to elaborate more on John’s character, but to get right to work. I experimented with playing with the ‘maximum length’ setting, as well as the ‘best of’ setting. Setting ‘best of’ to two or three generates two or three different completions, and returns the one to you that has the highest probability. But this also means you’re using more of OpenAI’s resources, so it’ll eat your credits faster.

I ran this a few times, and I like this result best:

Amy: This is the archaeologist's handbook to life.

John: What's it about?

Amy: It's about how to find ancient artifacts, and how to preserve them for future generations.

John: Sounds boring.

Amy: You're just saying that because you don't have an archaeologist's handbook to life.

That’s actually funny! (Admittedly, in a dad-joke kind of way. But still!)

The Artwork

Now let’s generate some artwork. We’ll use DALL-E, also from OpenAI, available here (since you already have an account and are presumably logged in, you’re taken directly to the generator page). We’re going to describe the kind of panel we want. Since our comic is pretty short, we’re going to try for a three-panel comic. Again, you’ll have to experiment to get the kind of look you want. It can be helpful to mention styles or artists whose work you want to emulate (…which also brings up thorny questions of copyright and consent!). I went with this:

A three-panel comic featuring archaeologists Amy who is studious and John who is a goof as they chat in an archaeological laboratory. Marvel

DALL-E is trained by feeding it masses of imagery culled from the internet paired with short descriptions. It decomposes these images to patterns of static, which it then associates with the words (and the words are associated with each other rather like how GPT-3 approaches things). Here is an interactive exploration of how that all plays out for a similar model, via the folks at Nomic.ai.

When you give DALL-E or similar ‘diffusion models’ a phrase, it examines the ‘space’ that these words occupy, and extrapolates the relevant pattern of static, from which it then evolves the resulting image. Intense, eh? See this piece by Eryk Salvaggio for a much better discussion of how this process works.

You can select from the results, and ask DALL-E to generate variations; eventually you’ll find something you like. It might be nightmarish. There are other generators you could try.

At this point, you can use a photo editor like Photoshop or Pixlr to edit out DALL-E’s wonky attempt at text, and put the text that GPT-3 generated into it. Et volia! You’ve used GPT-3 to make a comic, and another similar model to generate the artwork. (I tried to indulge my interest in archaeology and the uncanny by generating a Lovecraft-inspired horror/archaeology/ancient history mashup here using this approach.)

Where’s the history?

In the particular comic we just generated in the previous section, there wasn’t much ‘history’ per se. (If you dig into the details of OpenAI’s documentation, you could for instance fine-tune GPT-3 on a series of academic articles about Louis Riel, and then create a question-and-answer bot to power a website; that would be something ‘obviously’ historical. Really, the potential for AI and history is enormous; have a look around, and see what inspires you.)

But, staying with the comics/graphic novel theme, and with a little creativity, we could do something like this:

Louis Riel was a Canadian politician, a founder of the province of Manitoba, and a political leader of the Métis people.

He led two resistance movements against the Government of Canada and its first prime minister John A. Macdonald.

Riel sought to defend Métis rights and identity as the Northwest Territories came progressively under the Canadian sphere of influence.The first resistance movement led by Riel was the Red River Resistance of 1869–1870.

The provisional government established by Riel ultimately negotiated the terms under which the new province of Manitoba entered the Canadian Confederation.

However, while carrying out the resistance, Riel had a Canadian nationalist, Thomas Scott, executed.

Riel soon fled to the United States to escape prosecution.

He was elected three times as member of the House of Commons, but, fearing for his life, he could never take his seat.

Create the opening scene for a graphic novel about Riel's relationship with Macdonald.

I took the opening summary of Louis Riel’s life from wikipedia, pasted it in, and asked GPT-3 to summarize his life. I then used that summary in the prompt above. The result was this:

Riel is standing on the banks of the Red River, looking out over the peaceful landscape.

In the distance, he can see the smoke rising from the chimneys of the homes in Winnipeg.

He is thinking about how everything has changed since John A. Macdonald became the first prime minister of Canada.

Riel remembers when the Métis were in control of their own destiny and he wonders what will become of his people now that they are under the Canadian government's control.

Now you have a series of scenes that you could use GPT-3 to generate dialogue for, or artwork for; you could give it examples of Riel’s speeches and cadences and so on. Notice that I’m generating histories about very traditional topics in Canadian History. Remembering our discussion about the work of Saidiya Hartman, how might you craft ‘critical fabulations’ that follow her lead?

BUT, as students, as historians, we can’t just make things willy-nilly. Any creation you make with GPT-3 must be accompanied with your analysis of its design. Without that critical engagement, you are not doing history, you’re merely toying with it.